Article du magazine THE MEDAL NO. 54, 2010 (pages 30 to 35)

1. Nicolas Salagnac in his workshop, 2004 (Photo: © Jean-Luc Mège)

My occupation – engraver – is one of the oldest in the world. Yet it is currently going through a difficult period. Quality is the only thing that can restore this fine craft to its former glory. From my workshop (fig. 1) in the city of Lyons, the city in which the first French medal was struck over five hundred years ago, I fight to keep this expertise alive and to see the long line of engravers that links us to the past continue uninterrupted.

What made me decide to become an engraver and medallist ? As I child, I already knew that I wanted to do something manual that involved drawing. When I was not building play houses in the forest, I was often drawing, slowly but surely paving the way for my future occupation. School and I did not get on well together. My grandfather, one of the key figures from my childhood, once said to me: ‘When you grow up, you’ll go to the Ecole Boulle.’1 In 1985, after realising that I needed to work, I went along to this famous school and enrolled to become a cabinet-maker like my grandfather. However, as it turned out, I discovered a different material to work with and a whole new world : steel-engraving. My teacher Pierre Mignot rekindled my passion for drawing and manual work and, in the space of five years, taught me the technique of engraving.

In 1992, fresh out of school, I had my first taste of the working world, but it was not an easy one, for the craze for ‘pins’ (a type of badge) was at its height and there were few takers for traditional medals. In 1994 a subsidiary of the jewellery company Augis, founded in Lyons in 1830, was looking to replace the head of its engraving workshop. I was approached for the job, and so I left the capital of France for the capital of ancient Gaul, known in antiquity as Lugdunum. There I was shown works by Claude Cardot, a renowned engraver and medallist who in 1972 had won a Meilleur Ouvrier de France (MOF; Best Craftsman of France) award.2 Expectations were high and I needed to acquire specialised experience and to establish myself as the head of the workshop, while at the same time continuing to hone my engraving skills.

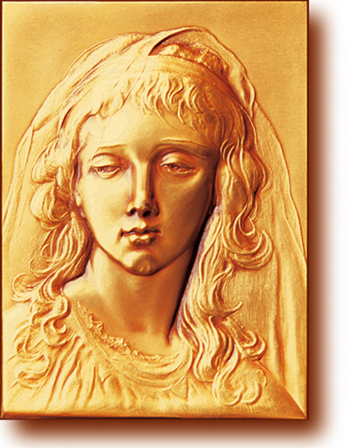

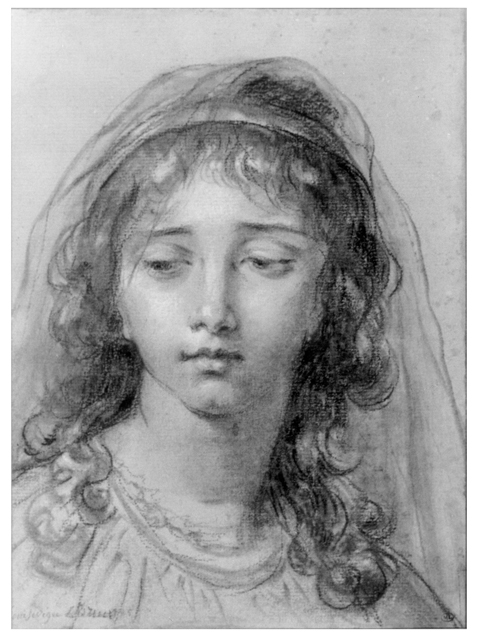

By 1997 I was ready for a change from the routine of the workshop and keen to learn more from my forerunners in the field, and so I resolved to enter the Meilleurs Ouvriers de France competition myself as an engraver. It took three years’ hard work before I was able to submit the two pieces required. One was a set piece – the bust of a young girl executed after a drawing by the eighteenth-century painter Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun (fig. 2) – and the other was an original design for one of the twelve labours of Hercules. The Vigée Lebrun set piece was for a steel punch or die, from which a medal could be struck (fig. 3). This handengraving was executed by tapping burins and gravers with hammers directly into the steel. The subject, though difficult, motivated me because of its richness. Translating this subtle and graceful drawing into an engraving was for me a sizeable but worthwhile challenge, as was the process of learning how to use traditional methods. This was a good opportunity to connect with the engravers of the past, who were more familiar with hand-engraving than are contemporary engravers. It bridged the gap between the generations.

2. Vigée Lebrun : Bust of a young girl, 18th century, charcoal and chalk, Musée du Louvre. (Photo: © Musée du Louvre)

3. Salagnac: Bust of a young girl after Vigée Lebrun, 2000, struck gilt bronze, 87 x 65mm. Struck by A. Augis. Two examples were produced in gilt bronze and two in unrefined, untoned copper. (Photo: © Nicolas Salagnac)

4. Salagnac : Hercules and the Nemean Lion, 2000, struck gilt bronze, 84mm. Struck by A. Augis. Two examples were produced in gilt bronze, and two in unrefined, untoned copper. (Photos © Nicolas Salagnac)

5. Presentation of the Villa Medici medal to Rita Levi-Montalcini, 2008. (Photo © Villa Médicis)

6. Salagnac : The Villa Medici medal, 2008, struck bronze, 90mm. Struck by Arthus-Bertrand. (Photo © Nicolas Salagnac)

7. Salagnac : The French president’s medal, 2008, struck gilt bronze, 90 x 90mm. Struck by Arthus-Bertrand. To date, ninety-five medals have been produced in gilt bronze and five in solid silver. They are issued in a leather presentation case with an accompanying booklet. (Photo © Nicolas Salagnac)

8. Salagnac working on the plaster model of the obverse of the French president’s medal, 2008. (Photo © Matthieu Cellard)

9. The production on a reducing machine of a steel die for Salagnac’s French president’s medal, 2008. (Photo © Matthieu Cellard)

The design for an original medal on the subject of a labour of Hercules was equally motivating and prompted me to delve into the new technologies applied to engraving and to test their advantages and drawbacks. However, after looking into the latest methods and giving the matter a great deal of thought, I decided to return to traditional methods, which might not be as fast but in which I was more proficient. The first step was to create a drawing. Next I produced a model on a 3:1 scale, which was reduced in the steel using a pantograph. I finished the work by going over the whole engraving by hand, and subsequently some medals were struck (fig. 4). These projects brought me into contact with craftspeople from a variety of backgrounds, and the inter-craft contacts that I forged were very enriching. In November 2000 my expertise was recognised by my peers – the competition is run by industry professionals – and I was awarded the prestigious title of a Meilleur Ouvrier de France. Fiercely determined to do a job that others are doing less and less, I set up my own business in 2003. I continue to persevere on the road to quality and, as I go, to conquer increasingly prestigious markets. My first official commission was for the city of Lyons. This was followed in September 2008 by a commission for a new medal for the Villa Medici, the home of the French Academy in Rome.3 The first official duty of Frédéric Mitterrand as director of the Academy was to present the first Villa Medici medal at a ceremony held on 5 December 2008 (fig. 5). The recipient was Rita Levi- Montalcini, holder of the Nobel prize for medicine and president of the Fondazione EBRI. The award was intended as a token of deep esteem and gratitude for the work of this Italian scientist, who is now a life-time member of the Italian senate, and the ceremony was attended by the president of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, the French ambassador to Italy, His Excellency Jean-Marc de La Sablière, and numerous other prominent figures. The obverse of the medal (fig. 6) presents a view of the Villa Medici as seen from its gardens, the building’s fine facade rising majestically while, under an umbrella pine, the ‘Eternal City’ with the dome of the Vatican is glimpsed in the background. The reverse shows the celebrated sculpture of Mercury, the messenger of the gods, by Giambologna, the Flemish sculptor who was for many years employed by the Medici court, dying in Florence in 1608. This commission was an honour for me, especially given the highly symbolic nature of the Villa Medici, which has played host to some of the finest French medallists, and I am grateful to have had the opportunity to become a part of the legend of a place that has nurtured the artistic and the beautiful for more than two hundred years.

My success in the Meilleur Ouvrier de France competition had demonstrated my expertise. Now I had to make it more widely known. Having designed and produced the new medal for the city of Lyons, on 31 May 2007 I wrote to the office of the new president of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, offering my services in designing a medal for him. Emmanuelle Mignon was quick to reply and express an interest in the idea. My first meeting with the president’s representatives took place on 15 September 2007, and I was given a free rein to submit proposals for the medal. I set to work, always remaining in close contact with the president’s office. The design that was finally accepted shows, on the obverse, the famous Elysée Palace and, on the reverse, various symbols of France (fig. 7). The Elysée Palace has been home to successive presidents of the French Republic since 1874. My representation of the façade is dominated by dynamic lines that dramatically underscore the perspective. Also included are the French flag, which recurs on the reverse, and the French Republic’s coat of arms. The words NICOLAS SARKOZY PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE (Nicolas Sarkozy, president of the French Republic) appear below, with the engraver’s name to the left. The reverse of the medal sets out France’s abiding values. The flag, flying vigorously and without restraint, takes up almost the entire surface, its volumes creating movement and vigour. This lively image coexists with the stars of the European Union. The words LIBERTE EGALITE FRATERNITE REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. French Republic) are written across the bottom. The engraver’s initials, along with Roman numerals indicating the date on which the work was completed, are shown on the right below the flag.

Once the low-relief models had been completed, impressions were taken in plaster, and these were then reworked by hand (fig. 8). Both sides were then reproduced on a steel block using a reducing machine (fig. 9). Once the machining was finished, it was time for a key phase: hand-engraving to remove all traces of the machine from the dies. I used a variety of tools here, including burins, which I tap with a hammer, scalpels, chasing tools and tracers. At this point I also redrew and emphasised the main lines of the designs. This finishing bears the distinctive mark of my hand and brings the future medal to life. On 15 June 2008, after nine months of hard work, I delivered my finished dies to the Arthus-Bertrand mint, where they were placed in a 1,600-tonne hydraulic press to strike on by one the silver and bronze medals. After striking, the medals were machined into a square shape and then toned. Only at the end of this long process, when all the different stages had been completed, could we speak of a finished medal. This medal is now presented by Sarkozy to eminent figures from around the world during official visits and receptions at the Elysée. It is an official gift from France. From my workshop in Lyons, it is with a certain pride that I see myself enter the small circle of engravers who have worked for the French Republic.

Frédéric Guignard-Perret has written about me in the magazine, Lyon Citoyen :

Raised in the love of traditional techniques, Nicolas Salagnac developed an insatiable appetite for work. With flair and a decidedly modern approach, he devotes his enormous talent to serving an art – and a philosophy of art – that are under constant threat from the uncompromising diktat of market economics. And this is how our fellow-citizen of Lyons etched a name for himself among the great … Using the same direct, tried and tested methods as the most prestigious and talented artists in history. In each of his creations, the engraver confirms, with class and humility, that man still holds the upper hand over matter. This is what he lives for, and his skilful, precise gestures impart life as if to transmit a soul, a spirit, a vision, a sensitivity and a movement that the weight of the solid metal reflects with not only force but grace, in both symbol and artistic value. Nicolas Salagnac’s creations have won a place in the hearts and lives of not only the greats of this world but also its ordinary people, bringing their creator the legitimacy and serenity that assure true artists of that rarest of gifts: a solid, enduring renown. The man himself – complex, racked by the obligation to excel, torn between his many activities to promote ‘the cause’, prey to doubt and a lack of assurance – must now wage a constant battle to convince himself that his name, his time and his style come at a price. The finished work is so striking, though, that its intrinsic worth is something customers not only understand and accept but also feel. Even if we know nothing of the complexity and difficulty of the production process and all that the artist has poured into its creation, we cannot help but be overcome by admiration for what is obviously distinctive. The result is there, before us, intense and self-sufficient, and commands respect.

»Yet this is a difficult time for Nicolas. Struggling with an aversion to anything resembling pretension, starved of recognition, full of humility and driven by a desire to pass on his skill, he is constantly striving to develop. He needs to stand back, come to terms with his talent, sell it at the right price, focus on the essential, channel his energy and strike the right balance between his work as an artist and his life as a family man.

There will always be people who love fine craftsmanship and who are happy to give or receive the fruit of the artist’s toil and creative spark rather than the impersonal costeffectiveness of high tech. Salagnac is the precious present of an art. He is also the future of our history. What more noble task ? Yet no-one will give him a medal for that. This little text is something of a personal tribute, ten years after our first meeting in the pages of this same publication. 4 »

Now, at the age of thirty-nine, I stand by my principles. There is only one way forward and that is to put the meaning back into work ; to remember the gestures, the tools and the know-how and to continue to learn how to use them, and then to pass them on; to strive for excellence, innovation and creativity; and to use this art to convey whatever is beautiful. This is what keeps me going.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to Sylvie de Turckheim-Pey, honorary head librarian at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and FIDEM delegate for France, for her invaluable help and her encouragement to persist with my craft. I would also like to thank François Planet, curator of the medal collection in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyons, for his sound advice. I am grateful also to Bernard Turlan, former chief engraver at the Monnaie de Paris, who taught me many things, and to Claude Cardot, MOF, steelengraver.

NOTES

»1. The Ecole Boulle is a renowned applied arts school in Paris, named after the cabinet-maker André-Charles Boulle. Since its establishment in 1886, it has provided training in art, design and industrial techniques.

2. Meilleur Ouvrier de France awards, often abbreviated to MOF, are made every three years to the best craftsmen working in France in various categories. The title was first awarded in 1924 and recognises a wide variety of crafts, from pastry cooks to carpenters, engravers to electricians. Candidates are required to produce a work in their specific area of expertise, a task that can take months, if not years, of preparation. Judges look for technical excellence, innovation and respect for tradition.

3. This French cultural institution is situated on Rome’s Pincian Hill and acts as a residence for young artists, helping them develop their creative projects. The French Academy was transferred to Rome by Napoleon I in 1803. Until 1970 the Villa Medici hosted the winners of the famous ‘Grands Prix de Rome’.

4. Frédéric Guignard-Perret, ‘Frappée de médaille’ Lyon Citoyen (February 2009), p. 15. »